Music and the Holocaust

As Holocaust Remeberance Day comes around on January 27, one of ACMP’s members, Dr. Leon Hoffman (Vc, Chicago, IL), reminded me how important it is to pay homage to all the musicians and composers who suffered so tragically during this terrible event. Several of the composers whose chamber music works are frequently played and cherished by our chamber music community were among those who were in persecuted groups and whose lives were changed forever. Here is a snapshot of some of those composers and their stories.

Alexander Zemlinsky was an Austrian composer, conductor and teacher. His pupils included Erich Korngold, Hans Krása, Alban Berg, Anton Webern and Karl Weigl, and he was friendly with Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg.

Zemlinsky had Hungarian Catholic heritage on his father’s side, and Jewish and Muslim heritage through his mother, but the family had converted to Judaism before Alexander was born. Zemlinsky converted to Protestantism in 1899 and, although he was not especially religious, he set religious texts and Psalms to music.

In 1927 Zemlinsky accepted an offer from Otto Klemperer to conduct at the Kroll Opera, and subsequently stayed in Berlin until 1933, guest conducting in France, Spain, Italy and Russia. On April 7 the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service excluded Jews from employment in the civil service. Zemlinsky wasted no time in leaving Berlin for Vienna in April 1933. The name ‘Israel’ was written in his Viennese residency application – whether he volunteered the information about his heritage is unknown.

Zemlinsky’s professional engagements ceased by 1935; whether he resigned by choice is unknown. Despite this, he composed prolifically throughout the 1930s, and received some performance and conducting opportunities in Vienna, Prague and Leningrad during this time. During 1936 he worked on his opera Der König Kandaules (King Kandaules), which had a libretto adapted by the French author André Gide, although he did not finish its orchestration. After the Anschluss in 1938, widespread attacks took place against Austrian Jews, and Zemlinsky and his second wife, Luise, destroyed photographs of Zemlinsky’s Muslim and Jewish grandparents, in case they could be used against him. The family was granted permission to leave Austria for the US thanks to the sponsorship of friends in America. They travelled through Prague, Rotterdam and Paris before arriving in New York in December 1938. They later found out that Luise’s mother and aunt had been deported to Terezín and perished in the camps.

In New York, Zemlinsky struggled to receive recognition for his work. He wrote a few popular songs, and his Sinfonietta was performed by the Philharmonic Society of New York in December 1940 and broadcast by NBC. Efforts to get his work Der König Kandaules premiered in at the Metropolitan Opera received little interest. He began work on a new opera, Circe, in 1939, but it was never finished. Zemlinsky’s health rapidly declined after he suffered a number of strokes, but he did meet Schoenberg for a final time – the composers had not seen each other since 1933, when they had allegedly argued over the application of twelve-tone technique. Zemlinsky died of pneumonia in 1942. Read more here.

Kurt Weill was born on 2 March 1900 in Dessau into a Jewish family with a long ancestry in Germany. As a teenager Weill began studying music with Albert Bing, and soon began composing, displaying the early predilection for vocal music that was to lead him to musical theatre. He later moved to Berlin to continue his studies, working with Engelbert Humperdinck and Ferruccio Busoni.

The aspiring musician quickly became a fixture in the vibrant cultural scene of 1920s Berlin. In 1922 he joined the Novembergruppe, a group of leftist Berlin artists that included Hanns Eisler and Stefan Wolpe. They primarily performed the works of modernist composers like Berg, Schoenberg, Hindemith, Stravinsky and Krenek. He had some early successes, but it was his partnership with Bertold Brecht that transformed Weill into an international sensation.

Like many other artists in his situation, Weill repeatedly misread political developments, believing that things were bound to get better. Eventually he learned that he and his wife were officially on the Nazi blacklist and were due to be arrested, so in March 1933 he crossed the border to France, still hoping that his stay in Paris would be temporary. Weill’s continued collaboration with Brecht while in Paris was relatively unsuccessful, and soon after his marriage ended in divorce. He then left for the USA, where he hoped to rebuild his career. There, he was also re-united with his ex-wife Lotte Lenya.

His first few years in America were fraught with difficulty – his plays were unsuccessful and the young couple struggled to support themselves. It was not until 1938, with his hit musical Knickerbocker Holiday written with playwright Maxwell Anderson, that Weill finally gained access to the musical theatre scene of Broadway. Despite his financial success in the United States, however, he never achieved the sort of fame or influence that he had enjoyed during the Weimar years. Always something of an outsider, he remained on the fringes of the musical establishment, and until his death was denied membership into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Weill died at the age of 50 on 3 April 1950. Read more here.

Bohuslav Martinů was a Czechoslovakian violinist and composer. Inspired by traditional Bohemian and Moravian folk melodies as well as contemporary music, Martinu wrote chamber music, operas, ballets, orchestral, and vocal works.

After the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939 and the signing of the Munich Agreement, Martinu tried to join the Czech Resistance in France but was not accepted because of his age. Instead he wrote a cantata for baritone, chorus and orchestra, Field Mass (Polní mše, 1939) in tribute to the Czech Government-in-Exile led by Edvard Benes and the Czechoslovakians fighting in the French army.

Field Mass was first broadcast in England and heard over the radio in Czechoslovakia. When the Nazis became aware of Martinu’s tribute to the Czech resistance, the composer was blacklisted by the regime. After the Nazi invasion of France in 1940, Martinu and his family were forced to flee because, as an enemy of the Nazis, Martinu risked arrest and imprisonment. The Martinus fled first to Aix-en-Provence in the south of France before crossing the border through Spain to Portugal in January 1941 and eventually fleeing by boat to the US. Composer Paul Sacher assisted with the Martinus’ financial costs.

Though Martinu initially struggled to settle in New York he soon adjusted and joined the teaching staff at Mannes College of Music and Princeton University. He composed prolifically in the US; he had not composed a symphony before arriving in America but wrote one per year from 1942-46. He also enjoyed premieres of compositions by leading American orchestras in New York, Boston and Chicago. In 1943 the New York Philharmonic premiered his eight-minute symphonic poem, Memorial to Lidice (Památnik Lidicím). The piece commemorates the 340 Czechs murdered by the Nazis in June 1942 in the village of Lidice. The piece premiered in an all-Czech concert on 28 October 1943, the anniversary of the formation of the Czech Republic in 1918.

Martinu became a US citizen in 1952 and returned to France in 1953 before accepting a teaching position at the American Academy in Rome in 1956. He died in Switzerland in 1959. Though he had been unable to return to Czechoslovakia during his lifetime, he was posthumously transferred to his hometown of Policka in 1979. Read more.

While never a practising Jew, Arnold Schoenberg’s (1874-1951) Jewish heritage had a significant impact on both his personal life and musical compositions. Schoenberg’s revolutionary musical technique of dodecaphony (using an ordered series of all twelve chromatic tones as the basis for a musical work) was his signature creation, and he often boasted that its modernist structure would secure ‘the hegemony of German music’ into the next century. Such nationalistic assertions would assume a sadly ironic tone in the inter-war period, during which anti-Semitic reactions to Schoenberg and his music became more prevalent and ultimately forced the composer’s emigration to America in 1933. When the National Socialists enacted the Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums (Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service) in 1933 which banned Jews from holding university positions,Schoenberg, then a professor of composition at the Akademie der Künste (Berlin), emigrated to America. He later accepted a position at the University of California Los Angeles.

In the years that followed, Schoenberg actively pursued Jewish issues and topics in both his essays and musical compositions. In the 1940s, despite his failing health, he continued to address specifically Jewish themes in three works: Die Jakobsleiter (1922; revisions unfinished); Moses und Aron (unfinished); and A Survivor from Warsaw (1947). Schoenberg died in Los Angeles, California, in 1951. Read more.

Visit Music and the Holocaust for all sources and many more articles.

To find chamber music by these composers, visit Find Chamber Music on the ACMP website.

If you would like to add content to this post, contact jclarke@acmp.net

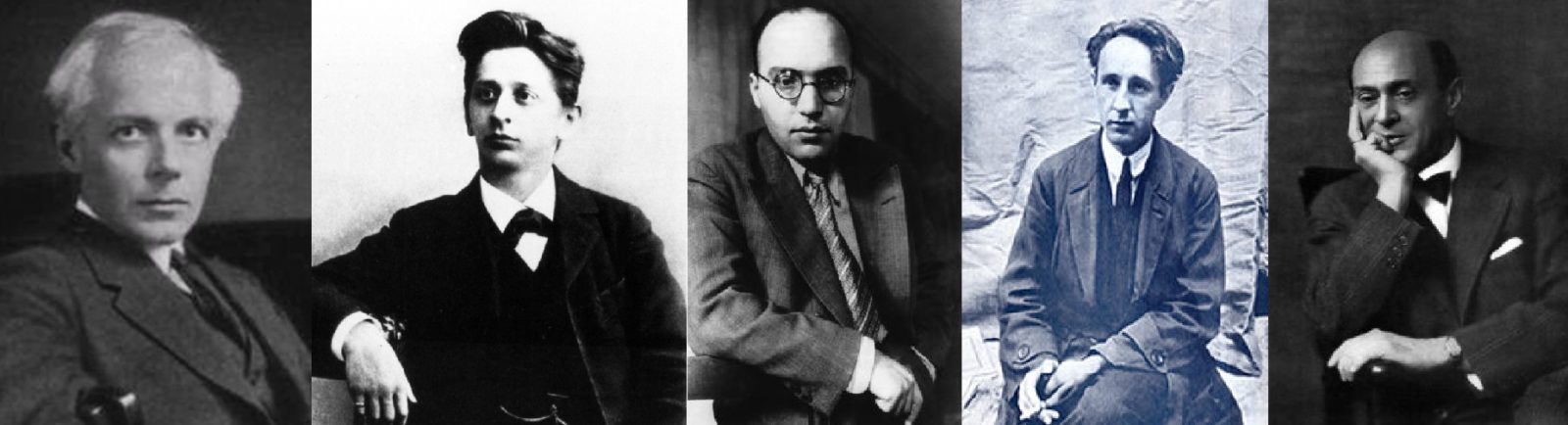

Header photo, from left to right: Béla Bartók, Alexander Zemlinsky, Kurt Weill, Bohuslav Martinů, Arnold Schoenberg

More Articles

Meet the Musician: Flutist Svjetlana Kabalin (Sunday, March 29, 2pm ET)

Join ACMP for an interview and Q&A with Svjetlana Kabalin on founding and sustaining Sylvan Winds and expanding wind quintet repertoire.Read More ↗

March Winds: Wind Chamber Music Appreciation Month

This March, ACMP is proud to launch "March Winds": Wind Chamber Music Appreciation Month! It's an international grassroots movement to expand the awareness and appreciation of the rich repertoire of chamber music including winds.Read More ↗

Kerry Graham: It’s never too late to learn the Baroque bassoon

At age 50, Kerry Graham was living what many would consider a rich and full life, working internationally as a chemical engineer and doing pretty well. But music, and especially the bassoon, kept tugging at her sleeve. She wanted to go back to school to learn the bassoon. Read Kerry's interview with ACMP Board chair Bob Goetz.Read More ↗

Helen Rice and me!

Professional flutist Jayn Rosenfeld grew up in a family of passionate amateur musicians and had a close personal connection with ACMP's founder Helen Rice. Read Jayn's story about her childhood experiences with some of the early pioneers of ACMP.Read More ↗

The 2026 ACMP Haydn Challenge

March 31 is Joseph Haydn’s birthday! It’s also a fabulous occasion to celebrate his contributions to the world of chamber music with a gift in his honor to ACMP…Throughout the month of March, we hope you will participate in the ACMP Haydn Challenge.Read More ↗

Irreverent Friends, the True Inspiration Behind Clarinet’s Chamber Music Gems

The Clarinet. When one thinks of the instrument, we are instantly taken on a rich journey of musical landmarks: New Orleans, Rhapsody in Blue, Mozart, Benny Goodman, top orchestras, your cousin’s wedding reception. Chamber music might not be at the top of the list, but indeed, clarinetists have inspired some of the finest pieces in history for the genre.Read More ↗

Sound and Sustenance: A Report from the Del Sol Adult Chamberfest

On a sunny weekend last month in San Francisco, 30 amateur chamber musicians from around the country gathered in the home of two members of the Del Sol String Quartet for the annual DEl Sol Adult Chamberfest. Neighbors would have heard strains of Britten, Janáček, Shaw, Golijov, Bunch, Beethoven and Brahms, along with laughter and good times!Read More ↗

New ACMP video: “Everything you always wanted to know about bows but were afraid to ask” with Gabriel Schaff

ACMP just released the video from Gabriel Schaff's recent online talk, "Everything you always wanted to know about bows but were afraid to ask." After an illuminating presentation on the evolution of the modern bow, the questions kept pouring in. There's so much to learn and discover from Gabriel and your colleagues in ACMP.Read More ↗

Mozart in a Brewery! Our First Young ACMP Event

Have you ever played Mozart in the middle of a brewery just for fun? That’s exactly what happened in early January when local Young ACMP members met up at Grimm Ales in Brooklyn. We co-hosted the event with ACMP member Ben Bregman, who brought music, friends new to ACMP, and a few of his young students and their parents.Read More ↗

ACMP presents the 2025 Susan McIntosh Lloyd Award to the SoCal Chamber Music Workshop in memory of Ron Goldman

This past Fall ACMP gave its 2025 Susan McIntosh Lloyd Award for Excellence and Diversity in Chamber Music to the SoCal Chamber Music Workshop in honor and in memory of SoCal's founder and long-time ACMP board member Ron Goldman. Watch my interview with Julie Park and read Adam Birnbaum's touching tribute to Ron.Read More ↗

Turning ink blots into music – a discussion on the meaning and madness of notation

Join Cal Wiersma and a live string quartet for an illuminating class about decoding musical notation and translating it back into a musical line, live in Brooklyn and live-streamed on YouTube.Read More ↗

A New 5-Day Summer Home for Adult Chamber Musicians in Brevard

Brevard Music Center is launching the inaugural Adult Chamber Music Workshop, June 3-8, 2026, and we could not be more excited to welcome adult amateur musicians to our beautiful mountain campus in Western North Carolina. The program features focused rehearsal time, inspiring coaching, great colleagues at your stand, and the simple joy of spending time immersed in chamber music.Read More ↗

Charles Hsu – oncologist, violist, luthier

Charles Hsu has packed a lot into his 33 years. Born in the New Jersey, he grew up in Taiwan, moved back to the United States to attend MIT, and, after a stint as a management consultant, pursued his medical studies at Yale and Harvard. Today, he is Dr. Hsu, a junior attending medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. But through all of these pursuits, there is his love of chamber music.Read More ↗

The Oregon-Washington ACMP Play-In

On January 17, 2026, 45 chamber musicians, ages 23-80, met at Portland State University's Music School Hall in Portland, Oregon for a Play-In organized by NAOC councilor Virginia Feldman.Read More ↗

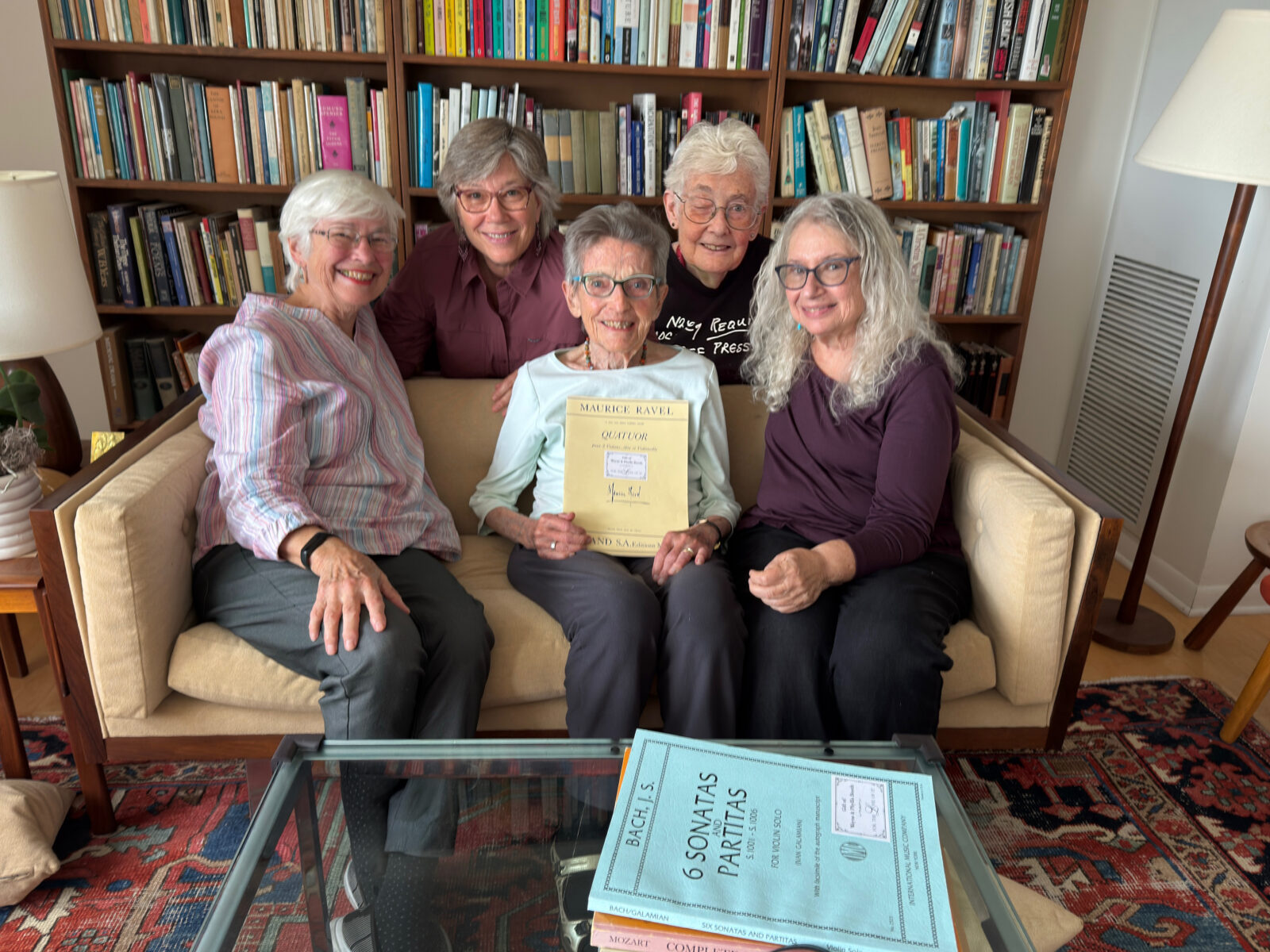

For the Love of It: A Legacy

What to do with all that music, when you finally, reluctantly, stop playing? At 99, Phyllis Booth decided to gift her collection to Golden Chamber Music at Sleepy Hollow, where she and her late husband Wayne Booth had a long, joyful connection since shortly after its founding in 1969.Read More ↗

Everything you always wanted to know about bows but were afraid to ask

Join Gabriel Schaff - violinist, scholar and author of "The Essential Guide to Bows of the Violin Family" for an illuminating journey through the history of the bow to everyday tips (no pun intended) about caring for your bow, choosing a new one - and....everything you always wanted to know but were afraid to ask!Read More ↗

Kayana Jean-Philippe: The serious business of an amateur oboist

When it comes to the oboe, Kayana Jean-Philippe is what you might call a serious amateur – someone who pursues her passion at a high level, but does not make a living at it. One of her most consistent musical outlets has been the United Nations Symphony Orchestra, which she joined 10 years ago and is principal oboist. Another musical outlet is ACMP, which she said has connected her with new people and new musical opportunities.Read More ↗

Announcing the 2025 Holiday Caption Contest Winners!

ACMP's 4th annual Holiday Caption Contest was a success, with 69 captions from 41 ACMP members. This year's winners are Valerie Matthews, Peggy Reynolds, and Matthew Greenbaum. Congratulations to everyone who came up with so many wonderful captions for this year's cartoon!Read More ↗

Announcing ACMP’s 2026 Workshop/Community Music Grantees

ACMP is proud to announce its 2026 Chamber Music Workshop and Community Music grantees. This year we awarded $168,000 in grants to 73 chamber music workshops and semester- or year-long programs in 10 countries, and 31 US states. (Photo by Claire Stefani.)Read More ↗

Mystery Donor Reveal: An interview with Louise K. Smith

An anonymous member of ACMP recently spearheaded a fundraising initiative for ACMP in the two week lead-up to Giving Tuesday, offering a $25 gift for each donation received from November 18, 2025 through Giving Tuesday (December 2.) This mystery donor just revealed her identity: Thank you, Louise K. Smith! I asked Louise some questions about her background as a pianist, involvement with ACMP over the years, and about her recent matching grant idea.Read More ↗